Peter de Francia once suggested that he only ever made two serious political paintings: The Bombing of Sakiet, which depicted a French military atrocity in Tunisia during the Algerian War, and African Prison (both 1959). To these, it feels necessary at the very least to add The Execution of Beloyannis (1953–54), responding to the death of a famous Greek Communist leader. These are ambitious works that harness the established genre of history painting to reveal contemporary inequalities or abuses of power. Here, perhaps, de Francia was following the injunction of Bertold Brecht (a figure he much admired) to ‘Begin from the bad new things, not the good old things’ – and yet, as de Francia stated in interview with his friend the writer and broadcaster Philip Dodd, his appreciation for the ‘good old things’ was always a rich vein of inspiration. In his great triptych of the 1960s, The Emigrants (1964–66; Tate), de Francia depicts an episode in the Maghreb that was ‘prompted by my hearing a story-teller on a ship telling a story to a group or groups of North Africans going to Africa […] To me, it felt as though it had something Homeric about it.’ He produced many paintings and drawings after figures including Pandora, Prometheus, the Minotaur – a focus on classical myth that was perhaps unusual for an artist committed elsewhere to social realism, though this was a dichotomy he would have rejected. His reading of modern poetry, too, was broad and deep – included in the selected works in this section are illustrations accompanying works by Césaire, Cavafy, René Char, the Czech writer Miroslav Holub, the Turkish poet Nâzım Hikmet and a remembrance of the great Surrealist poet Robert Desnos.

-

-

Oil sketch for The Bombing of Sakiet, 1959Oil on paper on canvas24.4 x 45cm

Oil sketch for The Bombing of Sakiet, 1959Oil on paper on canvas24.4 x 45cm

Sheffield Museums -

Figure Study for The Bombing of Sakiet, 1959Oil on canvas48.6 x 37.9cm

Figure Study for The Bombing of Sakiet, 1959Oil on canvas48.6 x 37.9cm

Sheffield Museums -

African Prison (study), 1959Charcoal on paper38 x 56cm

African Prison (study), 1959Charcoal on paper38 x 56cm

-

African Prison (study), c. 1959Charcoal on paper56 x 38cm

African Prison (study), c. 1959Charcoal on paper56 x 38cm -

The Survivors, 1963Oil on canvas182.4 x 121.3cm

The Survivors, 1963Oil on canvas182.4 x 121.3cm -

Head (Emigrants), 1964Charcoal on paper97 x 74cm

Head (Emigrants), 1964Charcoal on paper97 x 74cm

-

The Emigrants (left), 1964–66Oil on canvas182.3 x 106.5cm

The Emigrants (left), 1964–66Oil on canvas182.3 x 106.5cm

Tate -

The Emigrants (centre), 1964–66Oil on canvas182.6 x 106.1cm

The Emigrants (centre), 1964–66Oil on canvas182.6 x 106.1cm

Tate -

The Emigrants (right), 1964–66Oil on canvas182.3 x 106.1cm

The Emigrants (right), 1964–66Oil on canvas182.3 x 106.1cm

Tate

-

Hallowed Rituals (Mutilés de Guerre or Dulce est decorum), c. 1970Oil on canvas135.7 x 120.9cm

Hallowed Rituals (Mutilés de Guerre or Dulce est decorum), c. 1970Oil on canvas135.7 x 120.9cm -

Hallowed Rituals (Sharp Practice), c. 1970Oil on canvas121 x 136cm

Hallowed Rituals (Sharp Practice), c. 1970Oil on canvas121 x 136cm -

Ship of Fools, c. 1972Oil on canvas76.3 x 54.5cm

Ship of Fools, c. 1972Oil on canvas76.3 x 54.5cm

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

-

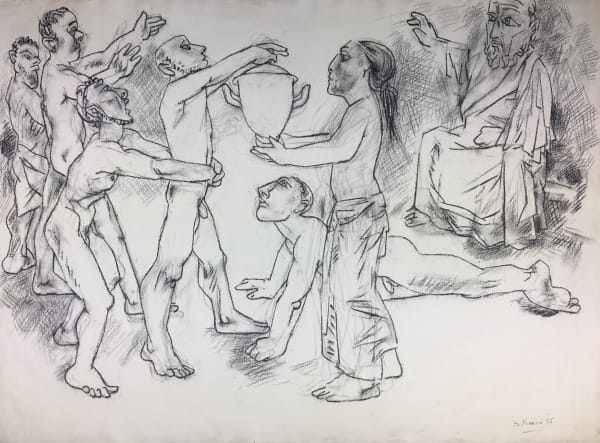

Illustration for Aimé Césaire's Diary of a Return to the Native Country, 1978Charcoal on papert63.3 x 49.2cm

Illustration for Aimé Césaire's Diary of a Return to the Native Country, 1978Charcoal on papert63.3 x 49.2cm

Museum of Modern Art, New York -

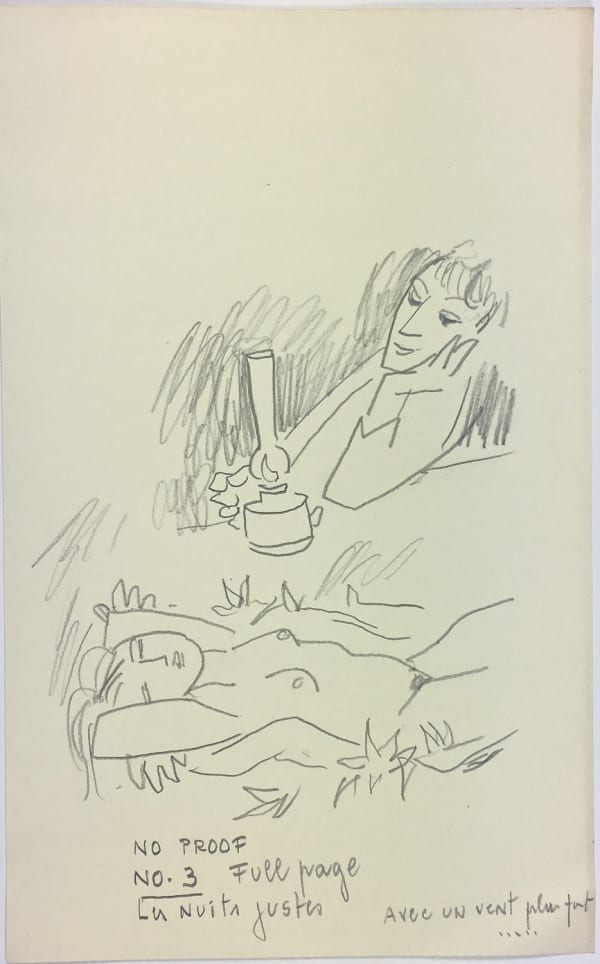

Drawing after a poem by Nâzım Hikmet, c. 1970s?Ink on paper24 x 33cm

Drawing after a poem by Nâzım Hikmet, c. 1970s?Ink on paper24 x 33cm -

Prometheus Steals the Fire, 1982Graphite and ink on paper55.9 x 76.2cm

Prometheus Steals the Fire, 1982Graphite and ink on paper55.9 x 76.2cm

Tate

-

Prometheus 1, 1984Drawing54.9 x 64.8cm

Prometheus 1, 1984Drawing54.9 x 64.8cm -

Minotaur, 1984Charcoal on paper51 x 63.5cm

Minotaur, 1984Charcoal on paper51 x 63.5cm -

Pandora, 1985Charcoal on paper57 x 77.5cm

Pandora, 1985Charcoal on paper57 x 77.5cm

-

The Violation of Innocence: Boy with Butterfly, 1988Oil on canvas106.7 x 137.2cm

The Violation of Innocence: Boy with Butterfly, 1988Oil on canvas106.7 x 137.2cm -

The Violation of Innocence: Boy with Dove, 1989Oil on canvas107 x 138cm

The Violation of Innocence: Boy with Dove, 1989Oil on canvas107 x 138cm -

The Violation of Innocence: Lovers, 1989Oil on canvas106 x 137cm

The Violation of Innocence: Lovers, 1989Oil on canvas106 x 137cm

-

Boy with Butterfly, c. 1988Charcoal on paper46.1 x 59.5cm

Boy with Butterfly, c. 1988Charcoal on paper46.1 x 59.5cm -

Drawing after a poem by René Char, c. 1980s?Graphite on paper40 x 25cm

Drawing after a poem by René Char, c. 1980s?Graphite on paper40 x 25cm -

The Visitation, 1989Charcoal and graphite on paper72.2 x 108.2cm

The Visitation, 1989Charcoal and graphite on paper72.2 x 108.2cm

Imperial War Museum, London

-