New Statesman and International, 9 June 1989

PHILIP GUSTON WAS BORN in Montreal in 1913, one of seven children of a poor Jewish Los Angeles where Guston received his early training via a correspondence course in cartooning. Influences of the visual language of cartoonists permeate his late work.

Guston moved to New York in 1935, joined the radical John Reed Club and enrolled as did many other artists-in the Works Programme Administration, doing public murals. A small number of surviving drawings and watercolours from this time are on show in the current exhibition Philip Guston: Works on Paper at Oxford's Museum of Modern Art (until 23 July). His early paintings and drawings include frequent references to the Ku Klux Klan. Throughout his life he retained a constant obsessive interest in early Italian Renaissance art and some of his most prolific periods of drawing were in Italy.

All Guston's work derives from drawing. In this he differs radically from the New York f painters with whom he is usually associated. For a period of some 14 years his paintings and drawings were purely abstract, and were identified as abstract expressionism: outside the United States—even after the dramatic changes in his work in the late sixties—he was known only through the paintings of the earlier decade.

The section of remarkable drawings included in this exhibition are inseparable from his paintings of this period. They are made up of probing marks, tentative notations, sometimes sparse or bunched together, skein-like. In the late fifties he was to emphasise the speed at which they were carried out. Some of the large paintings were completed in an hour. And he also referred to a “critical 20 minutes” of sustained concentration and emotion in the making of the works, adding “one of the great mysteries of the past is that such masters as Mantegna were able to sustain this emotion for a year”.

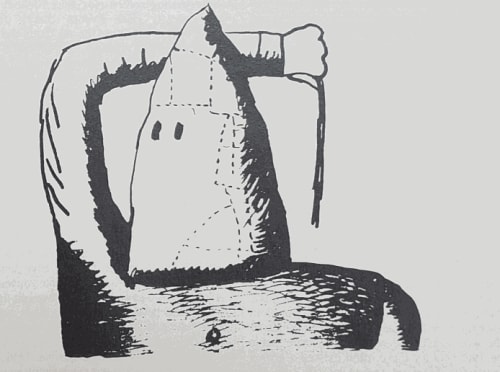

The inventory of images in Guston's late drawings is restricted. Deliberately so. He used improvised effigies of Toltec-like heads, makeshift constructions that are strikingly impermanent; repaired with strips of plaster, tape or of anything to hand. They are effigies to be feared or mocked at, placed as many of the images in his late works on a steep incline, as though about to roll downhill. A pun, perhaps, on Sisyphus? Often the foregrounds of his paintings and drawings are littered with debris: stones, fragments of urban junk-like, spent missiles on an empty abandoned terrain recently fought over in a riot.

Single objects are shown in isolation: a kettle like a trussed up-Brontosaurus. Others are grouped in a seemingly arbitrary way: bottles; cigarette stubs heaped in ashtrays; huge round heads like 20th-century golems evoking, perhaps, Guston’s Jewish upbringing; hooded clansmen, a direct link to his thirties work.

Eyeballs stare unblinkingly at naked electric light bulbs, illuminating with implacable exactitude an inventory of all there is to hand, all that is within reach, graspable, and all that can perhaps be relied upon. And it offers cold comfort. For in the fragments of walls included in many of these drawings—looped over with limb-like empty sleeves—or in flaccid legs nailed to ladders, trousered with implications of calloused knees, we are made aware that the slapstick satirical cartooning of Robert Crumb or George Herriman (whose work Guston admired and was influenced by) rubs shoulders with evocations of Buchenwald or Treblinka.

This imagery, used by Guston in the last ten years of his life, was first seen at an exhibition in New York in 1970, where it was received with hostility and seen as incomprehensible by critics and public alike. But it was here that Guston first revealed what he had sought and come to regard as “the real”. But, up until his death in 1980, “the real” was to take on a specific ambivalence: that of violent contrasts, a subversion of rationality through a language of seemingly dead-pan rationalism, located in a no-man’s-land in which compassion confronts satire and tragedy is often distinguishable from grotesque humour. Guston loved the objects and artefacts of the material world, but at the same time he was somehow horrified by them. This was both a dilemma and a catalyst.

He was an artist of superb integrity: his late visual language has been seen by some as providing a basis for a so-called “return to figuration” of a younger generation of painters, and his name has been associated with “new figuration”, “new objectivity” and various facets of zeitgeist. Aspects of his late works have, of course, been expropriated. But painting “rough” is essentially different from painting dumb — a difference seemingly ignored by some of his so-called followers.