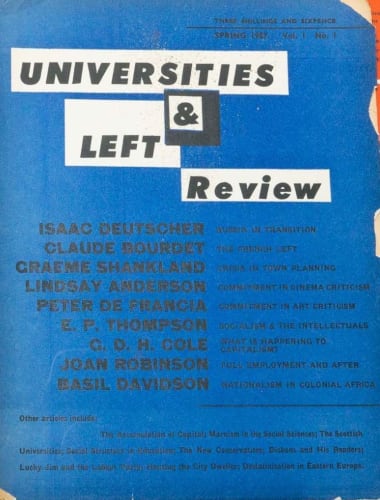

Universities and Left Review, 1957

“But, instead of your political ideas, said Monsignor Corbelli, you find among us the enjoyment of fine arts.”

“It is as though, replied don Françesco, you asked me to dine on coffee and sherbet. The necessities of life are freedom, individual security: the arts, in the nineteenth century, are only a last resort… We aren't happy enough any more to ask for the beautiful: all we want, at the moment, is the useful. Society is going to spend I don't know how many centuries pursuing the useful.”—STENDHAL.

“Art without ideas is a man without a soul: that is to say a corpse.”—BIELINSKI.

“Artists make new eyes: art critics, spectacles.”—ELUARD.

WHAT ARE USUALLY DESCRIBED as “bourgeois standards” in art were not established by any deliberate process of training. The bourgeoisie has discarded standards by the simple process of inventing a series of personal reactions applicable to the language in which most criticim is written. What the critic X “feels”, interpreting what the artist has “felt”, is in turn registered as a kind of confidential message by the “public”. The critic is a cross between a tick-tack man and a shamanistic interpreter of omens. The systems break down, of course, when the very nature of the work to be criticised enters the realm of pure interpretation. For example, to transmit the meaning of an “action painting”, involving as this does the intrusion of an interpreter between what has been called “utter directness” and the spectator, is an anachronism. The critic can be as uncommitted as he cares to proclaim, he is forced to say something about the splash of brown umber on the canvas. He cannot fall back on the stock items of comparison and historical analogy. Croce fails him. Even a reference to Bergson might be misunderstood. He will in all probability describe, at length, his pleasurable sensations. It is significant in this context that the forms of visual art which have the greatest appeal to the uncommitted bourgeois critic are all, in completely different ways, those which cannot possibly dent, scratch, or even remotely affect his position or ways of thinking. Spontaneous or action painting cannot do so, because nihilism is beyond him. Neither can he be moved by a picturesque expressionism—having nothing in common with the greatness of that movement—for displays of muscle-flexing fascinate him, and at heart he is a masochist, Suave graffiti fascinate him too: he feels he could have done them himself. Bottle-smashing comforts him, for like the visiting Minister of Housing he knows he will be home for dinner. He is committed to judge impartially. As a result, in the words of Bernanos, he is as dead as a pair of scales at even balance. We are indeed very far from “The streets will be our brushes… The squares our palettes”.

The vast majority of critics writing today are, in spite of the labels, totally committed. They are com- mitted to the task of perpetuating a system of reasoning, based largely on 19th century aesthetics and history, which assumes that each fresh individual form of expression, each burst of experimentation is invested, in an obscure way, with a revolutionary content. This conception implies the existence of a perfectly established order, and consequently of one or more firmly entrenched styles. A reaction against such order, on the part of the individual innovators of various sorts, would be normal and might be profoundly creative. Unfortunately no such conditions exist, and revolution is not a mood nor an abstraction.

Whatever the merits or the possibilities of a general theory of aesthetics, such theories in the past depended on philosophers. They, in turn, with the exception of Plato and Diderot, were not artists but aesthetes. Most contemporary critics share their “systematic” errors, but with an added difficulty arising from a completely vague aesthetic vocabulary—Mr. Focillon's “the life of forms”, or Mr. Alloway's “the projection of a new dimension”. Faced with the problems set by works which aim either at popular iconography, social comment or dynamic revolutionary saga, the critic usually ridicules the work, chides it or minimizes it. Occasionally another, more subtle method presents itself: the artists can be lumped together and deposited in that strange ante-room of the millenium invented by Mr. Colin Wilson. Nothing neutralizes so effectively the power of polemical and social attack, nothing can be so comforting as the implication that the artist responsible for it is in some way outside the pale—a blood brother, in fact, of the uncommitted.

Reduced to the role of interpreting private manifestations of originality, most contemporary criticism is naturally slanted towards a curious conception of the progress of vision and interpretation: that the art of Masaccio represents an advance on that of Duccio, Leonardo on Masaccio, Rembrandt on Leonardo, Cézanne, Picasso, and so on till 1957. In other words, that each artist should be another’s primitive. It corresponds perfectly to the essential mechanical vulgarity of a society which prides itself on spiritual heritages, and vaguely believes that progress, though doubtful in matters of economics and national prestige, may be relied upon in art. No cultural beliefs held by a minority with in a society have ever rested upon such slender foundations.

Abdication of critical standards

By this I do not mean to imply that all critics writing today are deliberately falsifying an existing situation. But what all critics and art historians deny and violently reject is a set of critical standards, definite premises upon which to base judgment and analysis, a refusal of personal intrusion and a form of writing which, in our time, cannot be anything but polemical.

The situation in England is still more complicated than elsewhere. The idea that intellectual movements could carry weight, be heard, produce as they inevitably must do the fundamental changes in outlook, vision, and liberty in a society, is here an atrophied belief, rejected with complete frankness by the critics. It is rejected on the grounds that intellectuals in England have not so it is said that tradition of assuming leadership, do not and cannot have the same position as those in relatively “backward” countries with an intellectual and student élite. This attitude has produced, since the thirties, a mentality close to that of a national minority group, clinging desperately on to trivial and rather absurd habits and customs but with a significant difference: the national minority group does, always, believe in a fighting chance of survival, and shows no interest in obituary columns. The most urgent task of critics writing in this country today should be to combat this attitude on the part of the intellectuals, quite apart from elucidating the intentions of the artist. Naturally one runs up here against all the old red herrings-the idea that the critic should be a mere intermediary, that criticism is invalidated if it is “more interested in ideas than in people”—as though the two can be separated—and, inevitably, the question of Marxism.

The reconquest of intelligence

Within the past five years a great deal of discussion has gone on concerning painting and sculpture. All other arts are involved, but the visual arts have been the focal point of debates concerning commitment, realism, social questions and the whole set of associations which these ideas immediately touch off. John Berger's articles in the New Statesman and Nation were the source of many of these arguments. The critical vocabulary used by Mr. Berger—the premises from which he criticises and many of the sources from which he quotes—proved to be utterly unknown to a large number of critics, and, because he employs words like “formalist” and “content”, he quickly came to be regarded as a kind of homicidal iconoclast. His attempt to instil some kind of social responsibility into criticism and, with only few exceptions, the consistently high level of his criticism have produced two results. They have shown that, even in the 500-word gallery lottery, art criticism could still be more than a game; and that the campaign he waged produced practically nothing in terms of painting or sculpture. In other words, his committed criticism reached the point where it started an inquiry into the terms of critical analysis. It failed, very largely, to reach the artists. I believe that the very mechanics of contemporary journalism are partly responsible for this; and, even more, that the critics, by consistently refusing the role of guide and confining themselves to that of observers, have made it impossible for serious artists to pay the slightest attention to what most of them write. The serious ones have been driven by an honest attempt at impartiality into a position of total ambiguity. The less serious ones owe their existence to the fact that the whole publicity machine has reached the point where two lines in the press can radically determine the success or failure of an exhibition: they are the call-girls of the profession. Imagine the difficulty, for instance, of any fundamental discussion of the sharpness and actuality of Diderot's “Paradox of the Comedian” being carried on at the moment-in connection with painting, sculpture or, for that matter, anything else. We have, it is true, passionate exchanges in The Listener on the height at which a piece of sculpture should be shown . . . three feet, ground level? a base? a pediment? The art institutes plod on, adding derivations to derivations. The critics toil forward adding interpretations to interpretations.

The re-conquest to be made in all the visual arts, amongst many lost realities, is that of intelligence. In one of the most moving letters that Van Gogh ever wrote concerning his predicament, he affirms his desire to be committed, and, writing of 1848 in 1884, he refers to the inescapability of personal decision by the phrase “the windmill has gone, the wind is blowing still”. This is exactly the image that every objective critic should have before his eyes at the present time. His commitment should consist of his entire critical force being brought to bear on the causes of artistic chaos rather than its manifestations, explaining rather than interpreting. In a recent letter Sir Herbert Read raises the question whether in criticism “it is more important to elucidate the intention of the artist than to pander to the sensations of the spectator. I may be wrong, or there may be two types of criticism, but I still think... that the creative intention of the artist (and the poet or the composer) is the line of approach that is more likely to lead to the discovery of important truths”.

It seems to me that this is an exact description of the very nature of the contemporary inadequacy of the uncommitted. No one in their senses would suggest that the anonymous spectator should be “pandered to”, but why conceive of the two forms of criticism as separate, as opposites? Do Daumier’s “intensions” have to be elucidated in the “Rue Transnonain”, those of Signorelli in the Last Judgment at Orvieto, Goya's in “May 2nd”? The value of the interpretative factor in art criticism can be far more easily defended in the sense of past art history than in contemporary terms. But art does not exist for the sake of either interpretation or art history, let alone criticism. My quarrel is not with “interpretation”, certainly not with attempts to elucidate particular problems that occur in ritualistic or mystical manifestations of the art of artistic creation. It is with the a priori acceptance of the fact that such interpretations are an essential feature of art because all art is by its very nature ambiguous. The public, in fact, do not always need “pandering to”. Van Gogh is far from being an “easy” painter. His work is full of radical “deformations”, colour transpositions and perspective arrangements. Yet he is probably one of the most “popular” of all painters. If I make an analogy between certain gestures and expressions of grief and anguish in Giotto's “Massacre of the Innocents” and “Guernica”, I am neither attempting a mechanical comparison nor interpreting the “point of view” of Giotto or Picasso. I am trying to establish, in the historical contexts of late Gothic and of the Spanish Civil War, certain features common to man's confrontation with violence and death. In Sir Herbert Read’s view, the “anonymous spectator” is relatively unimportant. In the view of certain critics of considerably less intelligence and honesty, he is simply despised. It can equally well be argued that any failure on the part of the public to understand or appreciate such works of what Stendhal called “la moralité construite” is entirely due to the ruthless swamping of men's vision by the crudities, pettiness, and grotesque absurdities of a social system created out of advertising, privilege swapping and cultural horse trading.

Nothing has been of greater service to the retreat into ambiguity, non-commitment and fear than the relative stagnation of art in Marxist countries, the mechanical nature of later Marxist criticism and, in certain cases, the perversion of Marxist cultural ideology, the basic premises of which seem to me more valid than ever. This stagnation is the direct result of a failure to understand the most elementary facts concerning the nature of experimentation, the treatment of art as a commodity, a gross over-simplification of the nature and uses of popular opinion. Soviet visual art has invariably swung from an attempt to express that which inconsequential) the tritest naturalism-to its own is immediately real (and often, therefore, completely particular formalism. True realism, which is the expression of that which is essential, has almost completely eluded it. Nothing could be more contrary to the very spirit of Marxism than an attempt in the immediate future, consciously or otherwise, to emulate certain features of the United States: a drive towards maximum technical efficiency in society coupled with the tolerance of experimentation in art, sanctified by the acknowledged doctrine that the purposes of art are therapeutic. It would perhaps have been possible for socialist societies to have taken, used and expanded certain aspects of Western painting in the thirties and to have retained their own innovators, limited though they were. The lowering of vitality in bourgeois art now make this impossible. But Marxist art and criticism have culminated in a tautology. Bourgeois idealism, chucked out of the door, has re-entered through the window.

The attack on chaos

Outside the baying of professional anti-communist journalists there is a desperate, pressing need to re- examine the whole course followed by the arts in Eastern Europe. The imaginary and the real are not irreconcilable enemies. They can be united for the purpose of hope and action. The nature of committed criticism is to effect such unity, here everywhere, with ruthless honesty.

To me there seems not the slightest doubt, in spite of the rapidity of political developments, that the cultural crisis can only deepen during the next few years: and with it, the crisis of criticism. It will continue, at least, in this country, beyond a period of profound social change. Increasingly nourished by art produced in perimeter areas—Brazilian architecture, Mexican painting, not in the so-called great artistic centres—it will become ever more difficult to adapt such influences to the growing shrinkage of the range of European bourgeois culture. This range can only decrease in exact ratio to the frantic affirmation of individuality. The game will be played till exhaustion.

Three methods exist, in visual art, of attacking chaos. The establishing of an unblemished, recurrent classicism, standing outside the direct influence of time but using certain basic contemporary symbols: the attempt, let us say, to create a pictorial or architectural morality. This is the kind of task that Léger set himself, by intelligent choice rather than by instinct. Second, an art of violent satire, usually of momentary circumstance, such as that used by George Grosz, or of violent exaggeration of collective or individual grotesqueness, such as that of the late paintings of Orozco. In both these cases the moral aspects of the work are dependent on the use of straightforward or inverted traditional moralities. Finally, there is an art of a deliberately social character, using a pictorial language which is extremely simple, and relying-like Guttuso’s entirely on dynamic content. The attempt here is to project, by sheer power of imagery, to establish a language of communication which lies outside a formula of aesthetics. It is understood, in such art, that morality is treated as a force created by the content of the work.

I have chosen to catalogue these types of work simply for convenience's sake; the list does not claim to include a great many works of profound creative insight, which, by implication, are polemical or iconoclastic, but which lie slightly outside these clumsy definitions: the early work of Rouault, for instance, or the graphic work of Barlach. The main point about all these artists is, how- ever, that they are a tiny minority when considered against the sheer mass of works being produced every- where, and that they are nearly all "unpopular", both with the "initiated" public and with the majority of the critics. This is not accidental and has nothing to do with impartiality or lack of commitment. Quite simply, these artists represent a menace to the very foundations of the bourgeois idea of art, and equally to the range of scholastic jargon which this idea has evolved.

The role of the critic who is convinced that art is a supreme manifestation of life, inseparably bound up with social and philosophical beliefs, is a simple one. To maintain criticism in the role of Lukac’s “skirmisher”, with all that it entails. To support, guide and encourage those artists who are experimenting, not for their own sake but to discover ways and means of establishing methods of expression which can provide at least a basis of discussion. For the role of the artist is not that consolidation, a thesis beloved by mechanical Marxist critics. At the moment, there is precious little to consolidate from. The great achievements of our time—Cubism, the work of Léger, Guttuso and Kokoschka, and the over-riding importance of Picasso—are rapidly becoming engulfed by the pictorial illiterates, the fake realists, and a torrent of general rubbish. And it is really very little use looking back in anger. It is more profitable to savour this emotion when looking in the other direction. Truth, as Brecht wrote above his door, is concrete.