‘His intelligence makes him a professional in an age of amateurs’ – John Berger, critic, novelist, painter and poet, 1958

‘I consider the stand that Peter de Francia has taken a correct and courageous one, and his painting of special significance in the current European art scene’ – Renato Guttuso, painter and senator of the italian republic, 1961–62

‘De Francia is a cosmopolitan, an artist who sees not only what meets the eye, but also what moves the mind’ – Dore Ashton, writer and critic, 2008

‘He is as it is a legendary figure – exactly in the way that the word is meant, part history, part fiction’ – Geeta kapur, critic and art historian, 1991

The monumental early canvases of Peter de Francia have long been recognised as social realism of the highest order. With The Bombing of Sakiet (1959, Tate, on long-term loan from the Tunisian Embassy) – a response to a French military atrocity in Tunisia that has often been called his Guernica – he realised an excoriating vision of the barbarism inflicted by so-called ‘civilised’ countries, imbued with a pathos that is unmatched by any British painting of the period. His work, indeed, sits rather restlessly within the tradition of ‘British painting’ – a testament to the cosmopolitanism of both his influences and his outlook. During his lifetime, he held major exhibitions in locations including Milan, New Delhi, New York, Prague – and, of course, London – while his bitingly satirical paintings and drawings called Disparates, after Goya, are to be found in museum collections across the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

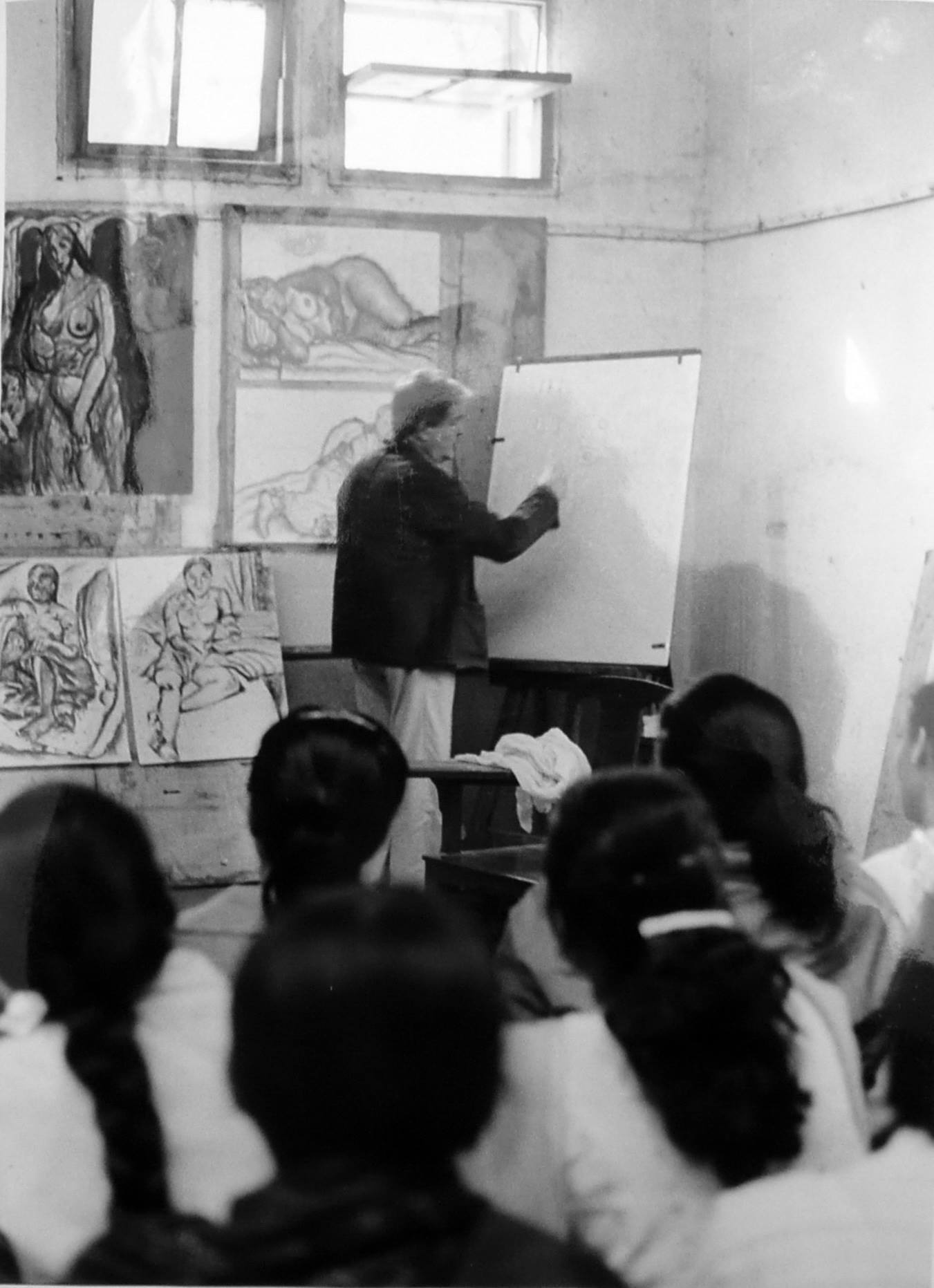

The full extent of de Francia’s painterly achievement is only now beginning to be understood – and it is by no means limited to masterpieces which, like Sakiet or his series of Disparates, are animated by the darkness and brutality of the world he found around him. ‘We desperately need luminosity,’ he declared in 1973, concluding the inaugural lecture he delivered on appointment to the post of Professor of Painting at the Royal College of Art, London. In an era defined by nothing so much as hollow spectacle and crass consumerism, the task at hand, he charged his students, was to instil painting – a form under attack for its ‘apparent archaism’ – with new intellectual and political rigour, thereby realising ‘a visual language tough enough’ to imagine a new (and ‘luminous’) society.

Over a career spanning seven decades, de Francia completed tender and intimate portraits of subjects spanning public intellectuals such as Eric Hobsbawm and unnamed sitters both young and old. He found beauty in the muscular gait of workers encountered in Italy, where he lived for a spell after the Second World War, or else in North Africa or at the quarries in Lacoste, the Provençal village where he owned a house from 1957. He found inspiration in the faces of migrant travellers, or the poise of Chinese acrobats, or the entwined figures of men and women on bicycles or Vespas. He illustrated works by poets ranging from Césaire to Cavafy to the Czech writer Miroslav Holub, as well as scenes from Greek myth: depictions of Pandora or Prometheus that meditate on rebellion, liberation and disorder. John Berger declared that ‘it is his intelligence that makes him a professional in an age of amateurs’ – but his work is also distinguished by his interest in the sensuous life, found equally in his nudes and his bucolic scenes of workers in repose.

What is most remarkable about de Francia’s enormously varied oeuvre is that it can all be seen as part of the same, lifelong project. It was never enough to hold a mirror up to the heartlessness of the world, as defined by the powerful; the prerogative of the painter was to realise an alternative. For de Francia, this alternative was not to be found by disappearing into abstraction, or through Pop Art’s fixation with consumer mass culture. His art, like his politics, was fuelled by the necessity of engagement with the world he found around him. That meant a commitment to figurative painting, although his touchstones in this regard were not the contemporaneous reinventions of that mode by the likes of Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud or David Hockney, but rather European agitators like Renato Guttuso, Fernand Léger, Picasso and, further back, Gustave Courbet and Honoré Daumier (he once called the latter ‘my father’).

De Francia was born in Beaulieu, a coastal town on the French side of the border with Italy, the son of a wealthy Genoese lawyer and an English mother, Alice Groom. He had a multilingual education in Paris before, following the death of his father in 1939, briefly commencing studies at the arts academy in Brussels. After the Nazi invasion, he cycled to the coast and successfully fled to his mother in England, serving in the British army by whom he was tasked with interpreting photographs of the Normandy coast. He attended the Slade School of Fine Art, though his immersion in the heart of the British arts establishment didn’t dampen his innate cosmopolitanism; he worked in the studio of the painter and Communist Party politician Renato Guttuso in Rome in 1947, the beginning of an important relationship for both artists; held solo shows in Milan later in that decade; and in 1950 met the German Expressionists Max Beckmann and George Grosz in New York. He was employed briefly by the Canadian Government Exhibition Commission, in the Architects’ Department of the American Museum in New York, and as a talks producer for the BBC.

Steeped in the European tradition, de Francia was well prepared to take an active and combatant role in the factionalism of British art and politics during the 1950s. His intellectual circle included John Berger, the scientist JD Bernal, Doris Lessing, the cartoonist Abu Abraham and many other pioneers of the British New Left; in 1957, de Francia helped to found the Universities & Left Review (now the New Left Review), contributing an essay to its first edition. He realised the first of three great modern history paintings in 1953–54 – The Execution of Beloyannis (Tate), a response to the death of the Greek Communist party leader Nikos Beloyannis at the hands of a military tribune. The killing of 79 Tunisian villagers by the French army during the Algerian War prompted his second, and The Bombing of Sakiet was followed in short order by the vicious sublimity of African Prison (1959; Sheffield Museums).

De Francia’s inaugural lecture for the RCA remains among the finest written elucidations of his vision, rivalled only by passages of the extensive monograph on Léger he published in 1983. He called the lecture Mandarins and Luddites – the former defined as the art-world gatekeepers, dealers and critics, whose narrow definitions of good taste ‘bedevilled independent artists in this country’; the latter, those who sought to do away with art entirely, believing it inherently elitist and, more fundamentally, useless. ‘What is a Raphael to a pair of boots?’, one 19th-century Luddite asked – to which de Francia rejoined, ‘neither should be luxuries, but both Raphael and a pair of boots are essentials’.

De Francia ruffled more than a few feathers at the RCA, described by one colleague as a ‘new broom’ who took, for instance, the outlandish step of ousting staff from the common room, where he felt they were all wasting too much of their time – but he also earned lasting respect for the fact that students during his tenure left the school with a much broader sense of their position within the European imaginative tradition. The student body was cosmopolitan, and de Francia was supportive of artists who had arrived from India and elsewhere to study. His standing was such that when, in 1980, the new rector Dickie Guyatt tried to fire him, it was Guyatt whom the school rose up in arms to send packing with a vote of no confidence.

John Berger called de Francia a ‘horizon-painter’, and the phrase is apt. When we look to the horizon, we find ourselves engaged in an effort to understand and to encompass the world as it exists around and beyond us – yet as a result, we are impressed with renewed appreciation of the ground on which we stand and the perspective that it grants us. To live a life at once expansive and grounded – that is the essential dilemma posed to us by the luminous art of Peter de Francia.

© Clive Barda

1921 Born, Beaulieu, Alpes Maritimes, France

1938–40 Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts, Brussels

1943–46 Slade School of Fine Art, London

1949–50 Canadian Government Exhibition Commission, Ottawa

1950–51 Architects’ Department, American Museum, New York

1951–52 Talks Producer, BBC Television

1953–68 Department of Art History and Complementary Studies, St Martin’s School of Art, London

1961–69 Department of Art History and Complementary Studies, Royal College of Art, London

1970–72 Principal, Department of Fine Art, Goldsmiths College, University of London

1972–86 Professor of Painting , Royal College of Art, London

1990 DAAD Fellowship, Berlin

1991 Visiting Professor, Baroda

1991 Visiting tutor, New York Studio School and School of Fine Art, Nicosia, Cyprus